Good Neighbours, Bad Neighbourhoods

- Vidhi Sikarwar

- Sep 7, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 10, 2025

By: Vidhi Sikarwar, UG2023 ; Edited By: Krithi Kankanala

Why has segregation in Indian cities seen no improvement despite an increase in tolerance between social groups? This article dives into the mechanics of Schelling’s Segregation Model to explore this puzzle. It looks at how minor preferences can produce significant separation, while addressing the limitations that come with the model’s assumptions. Starting with understanding the Indian reality of segregation and why it matters, the article transitions into Schelling’s model to unpack its insights. Finally, it evaluates where the model fits and where it falls short in explaining India’s problem.

Indian Segregation: Tolerance Without Integration

Caste and religion, among other identities in India, continue to play a decisive role in determining where people live, and by extension, what opportunities they can access. Economist Sam Asher, associate professor at Imperial College London, finds that caste and religion-based segregation in India is as severe as racial segregation in the United States. Moreover, levels of segregation for SC communities are as high in urban areas as they are in rural ones.

On the surface, if segregation simply reflects people choosing to live among others “like them,” why is it a problem? Viewing this from a preference-based perspective, one might argue that if everyone is satisfied with their neighbours, the outcome is harmless. But in the real world,segregation is rarely harmless. It produces and reproduces deep inequalities, particularly for historically disadvantaged communities. Journalist Raksha Kumar notes that segregation based on caste and religion in India has clear and measurable impacts on upward mobility. When privileged groups dominate certain neighbourhoods, those areas tend to receive better infrastructure, schools, healthcare, and employment opportunities. Meanwhile, lower-caste and minority neighbourhoods, often pushed to the city outskirts, struggle even for access to clean water. Asher’s study, for instance, shows that Muslim and Scheduled Caste (SC) neighbourhoods receive significantly fewer government facilities, regardless of income. Segregation thus deprives already marginalised groups of essential services, creating a cycle of exclusion.

Here’s the puzzle.

While caste discrimination remains prevalent in India, explicit bias is declining, especially in urban areas. People in cities are much more accepting of other identities, especially disadvantaged ones, as compared to rural areas. So, if prejudice and biases in urban areas are reducing, why can’t we see a significant difference in segregation levels between cities and rural areas? Why does segregation persist despite an increase in tolerance and acceptance?

Let’s see whether a model from the 1970s can help answer this question.Let’s see whether a model from the 1970s can help answer this question.Let’s see whether a model from the 1970s can help answer this question.

Let’s see whether a model from the 1970s can help answer this question.

Schelling’s Model of Segregation: Why Tolerance Is Not Enough

Schelling’s model of segregation demonstrates how slight individual tendencies to have similar neighbours can lead to highly segregated societies. His model shows that even when individuals don’t mind being surrounded by people of different races, religions or economic backgrounds, societies can still become highly segregated as an emergent outcome.

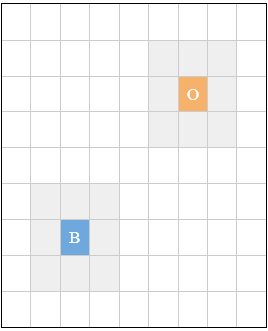

Schelling’s model looks at how individuals, or agents, choose their housing based on their immediate neighbours. The simplest model contains two types of agents, say B (blue) and O (orange). These can represent individuals from different races, religions, castes, socioeconomic standing, etc. The simulation starts with placing the populations of these two types of agents randomly on an N x N grid. Each cell is either occupied by an agent or is empty.

Grey areas show the neighbouring cells for each agent

Next, the simulation looks at whether each agent is satisfied with their position. Every agent has a desire to be surrounded by some people similar to them. This desire is quantified by a threshold t, which defines the minimum proportion of an agent’s neighbours that must be similar to them for the agent to feel satisfied. An agent is satisfied if t is met, in which case she doesn’t move. However, if t is not met, she will keep relocating to a random empty cell until she’s satisfied.

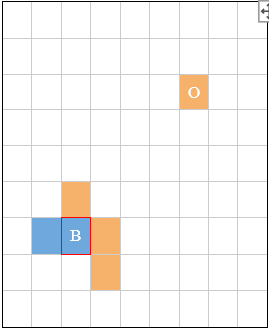

For example, take t to be 30%. This particular agent B will be satisfied as long as at least 30% of her neighbours are also blue.

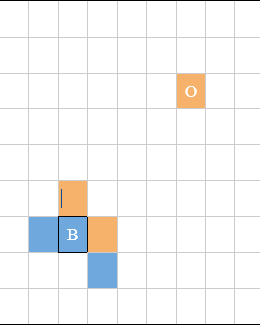

The dissatisfied B will keep changing locations until she’s satisfied, but note that her movement can cause other agents, who were previously satisfied, to move. For example, say this B moves next to an O that’s surrounded by one orange and two blues (33% similar neighbours):

Suddenly, we’ve got two new dissatisfied residents. O is dissatisfied because now only 25% of her neighbours are similar to her, while B’s previous blue neighbour has no one similar to her left. Thus, a chain of movement has to take place until everyone is satisfied.

Changing the value of t changes how tolerant people are about others - a higher t means agents are harder to satisfy, and as t approaches 0, agents care less and less about their neighbourhood’s composition. While it’s obvious that higher values of t will lead to more segregated outcomes, what’s surprising is that segregation emerges even for lower values of t.

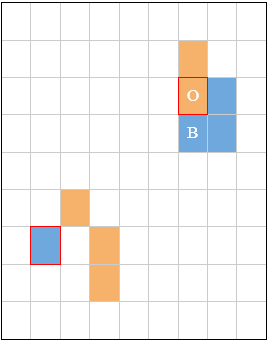

Schelling found that there exists a threshold ta such that for t < ta, the population gets distributed randomly, but for t ≥ ta, the population becomes segregated. In this version of the model, the value of ta is approximately ⅓. This model is therefore also referred to as Schelling’s tipping model, since a small change in t from t < ta to t > ta can “tip” a neighbourhood from being randomly distributed to being segregated.

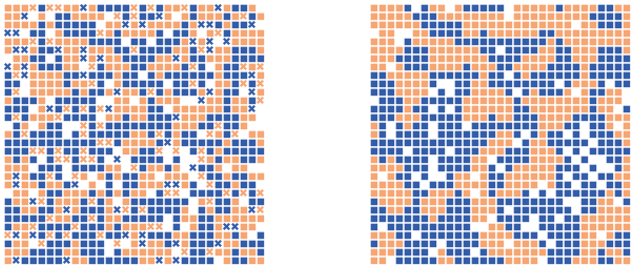

x represents dissatisfied agents

Starting point vs. Ending point of a simulation on a 15x15 grid with 90% density and t = 30%

(Images generated on NetLogo Segregation Model)

These results offer a great insight: just the desire to avoid being part of a small minority is enough for the emergence of segregation. Moreover, once segregation begins, it accelerates as people move to avoid being outnumbered, leading to tipping effects and polarisation.

Applying the Model to India’s Case

How well can Schelling’s model explain caste-based segregation in India?

While it is an oversimplification, there are parallels between the model’s predictions and India’s urban realities. Let’s start by looking at where the model fits.

Where it Fits

Results from Pew Research Centre’s report show that while people in cities are okay with living next to people from different castes and religions, segregation levels remain high. From Schelling’s model, we can deduce that perhaps being tolerant of other identities is not enough to avoid segregation, as mild preferences for similar identities are enough to drive social clustering. While not overtly visible, in India these thresholds could instead manifest through coded preferences, such as vegetarianism, language, education, or profession. The preference for vegetarianism can act as a stand-in for upper-caste Hindu communities, while language preferences drive segregation based on regional roots. The desire to be surrounded by families with similar education levels can also cause separations based on caste and socio-economic background.

People also have different personal thresholds of tolerance (t), which can make societies reach the tipping point (ta) much faster. As families from marginalised groups move to cities for better opportunities, they might cause some people with higher thresholds to move away. As they leave, they trigger others with lower thresholds to move away, as the ratio of similar to non-similar drops. And once neighbourhoods reach the tipping point, they’re perceived as “too Muslim” or “too SC/ST”, further dropping property demand from dominant castes/religions. A reduction in property values consequently leads to disinvestment, meaning the families moving in are mostly from marginalised groups, feeding back into the forces causing the segregation.

This model shows that individual acceptance isn’t enough; large-scale segregation can still arise from the self-preserving preference to avoid being in an extreme minority. People may not be casteist, but the tiniest preference to have some neighbours ‘similar’ to them can drastically affect macro outcomes. Good intentions are not enough to prevent harmful systemic outcomes.

Where it Breaks

Schelling’s model is elegant in its simplicity, but like any other model, it comes with its own set of assumptions. With active exclusion, historical injustice, and structural inequality, the real world is much more complex. So, where does India’s case deviate from the model?

The most prevalent diversion is in the reality of preferences. In Schelling’s model, mild, homogenous preferences lead to segregation as an emergent outcome. In India, preferences are neither homogeneous nor mild. While cities have overall grown more tolerant, not everyone shares the same level of tolerance. For example, in Pew’s report, 36% of Hindus said they would not be willing to live near a Muslim, while 31% do not want to live near Christians. Adding on, around 41% of Jains said they would not be willing to accept Dalit neighbours.

The active exclusion that these attitudes foster further feeds into the segregation of communities. With minorities facing harassment, violence, and crimes against them due to such biases, Schelling’s model is unable to account for the unequal power dynamics at play. The model also assumes freedom of choice when it comes to housing, which is far from reality. Dalits and Muslims are often denied housing in certain establishments based on their identity.

Schelling’s model also cannot account for the history of segregation in India. While the model always starts from a blank slate, India has seen centuries of exclusion - from classical village layouts to town planning during the British colonial era. Historically, Dalit communities have been pushed to the outskirts of villages and cities, while upper castes have dominated the centre. When a country has always seen such extreme levels of segregation, looking at a reduction of individual thresholds can be of little help.

Conclusion

Segregation in India, especially on the basis of caste and religion, is more than a legacy of the past; it’s today’s reality, even for cities that pride themselves on progress. Schelling’s model unveils how mild individual preferences can create large-scale segregation and offers a valuable insight - good intentions aren’t enough; they’re elementary. However, India’s context also reveals that deeper structural forces, like active discrimination, unequal power, and historical exclusion, go beyond what this simplified model captures. In Schelling’s model, segregation is emergent. In India, it’s both emergent and enforced. So the natural question to ask is, if mild preferences alone can cause segregation, and deeper structural forces only worsen it, then is shifting these preferences the first step? Can policy succeed with only tolerance, or does it need a social will for integration?

Comments